Jerry Flint, with the 4th Wisconsin Infantry in Louisiana, has a lot to say in this letter about past experiences, what’s happening currently around him, and what he expects in the near future. The original letter is in the Jerry E. Flint Papers (River Falls Mss BN) at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, University Archives and Area Research Center.

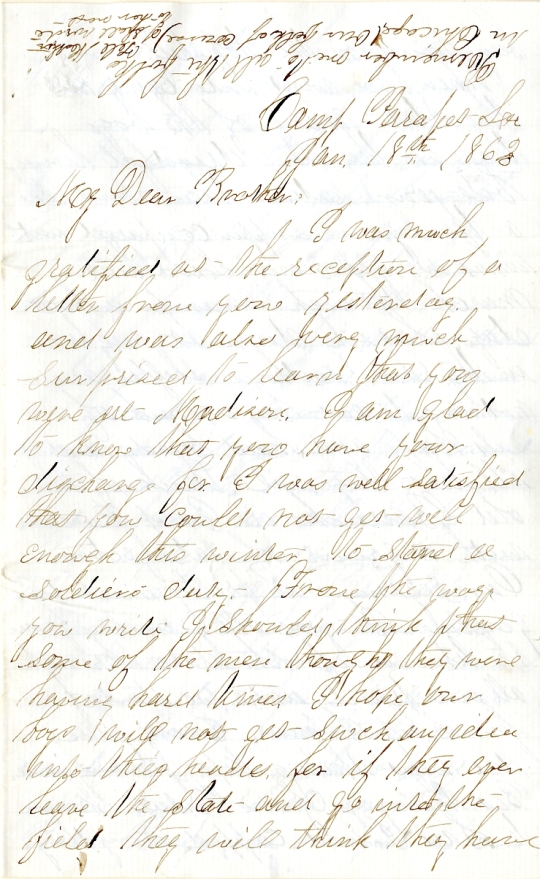

Camp Parapet La

Jan. 18th 1863

My Dear Brother,

I was much gratified at the reception of a letter from you yesterday, and was also very much surprised to learn that you were at Madison. I am glad to know that you have your discharge for I was well satisfied that you could not get well enough this winter to stand a soldier’s duty. From the way you write I should think that some of the men thought they were having hard times. I hope our boys will not get such an idea into their heads, for if they ever leave the State and go into the field they will think they have been living on the top shelf.

When we went into camp in the State many of the boys thought they had dreadful living but our rations then were like thanksgiving supper compared with what we get now. Let them march through the swamps a few days, laying down at night in the rain without shelter and nothing to eat but a chunk of salt beef and hard bread, and ill lest they will think of the old Barracks at Camp Randall with a grunt of satisfaction. [paragraph break added]

Our regiment is pretty much done growling. It was all grumble from the time we left the state through all our travels until we started for Ship Island. Every place we went things kept growing worse. But the voyage from Fortress Monroe to Ship Island capped everything before it so the boys came to the conclusion that they might just as well keep cool and take things as they come.

There has been many times this summer when I would have been glad to have got out of the service, but I could have done so honorably, but I never wish to leave while matters stand as they are now. I can never again feel proud of being called an American citizen if the accursed “Stars and Bars” emblem of treason and rebellion are allowed to float independently over the ruins of our once great Republic.

Things in the department are very quiet although our Generals are not idle since the arrival of Gen. Banks forces [Nathaniel P. Banks], troops are constantly moving about and getting ready to do something. Baton Rouge was occupied as soon as his forces arrived and there is now at that place an army of 30,000 men. They are mostly new troops and to use their own words don’t mean to fight much. They are enlisted for nine months and got a huge bounty.

I say curse such men.

Quite a number of the old regim[ents] are with them at Baton Rouge and I am afraid that when the battle comes they will have to stand the brunt. Our regiment is up there in a brigade commanded by Col. Paine [Halbert E. Paine]. Their position is in the advance. It was said when the regiment left that we should follow them in a week or so as soon as another company could be drilled on the heavy guns. But we are here yet and no more signs of going that first. We shall however probably join them before the column is ready to move.

It is expected that we shall have a severe fight at Port Hudson. The rebels have fortified until it is nearly as strong as Vicksburg. When we came by there the last time in July there was not a gun there. Now thousands of lives must be lost taking it. Why they were allowed to fortify right under the nose of our gunboats is more than I can tell. I think it could have been stopped any way.

Gen. Weitzel¹ has been fighting in the vicinity of Berwick Bay and has scooped the rebels every time. The rebel iron clad gunboat on Bayou Teche was blown up. Lieut. Com. Buchanan² of the gunboat “Calhoun” was killed by sharp shooters on the bank of the Bayou. His funeral was attended in New Orleans. Admiral Farragut [David G. Farragut] and Gen. Banks marched on foot in rear of the procession.

The rebels again have possession of Galveston but it will not long as an expedition is fitting out for that place. I do not know whether you have heard of the capture of the Harriet Lane and the destruction of the Westfield in Galveston Bay or not. They were both aground when New Years eve four light draught boats of the rebels came out and attacked them. The Harriet Lane sunk one of them but being aground she could not maneuver so that the rebels boarded her and after a severe fight captured her. They then made for the Westfield but Com. Renshaw [William B. Renshaw] seeing he could not help himself told his crew that the rebels could never have her and that all who wished could take to the boats for he was going to blaze her up. Part of the crew swore they would never leave their commander and so staid and were all blown up together. The Westfield was a light open boat but carried some good guns. She was up the river with us last summer. When the rebel ram Arkansas run the upper fleet and landed under the guns of Vicksburg this boat run right up under the guns, fired a shot into the ram as a challenge to come out and fight her alone but they dare not do it. This shows what kind of man Renshaw was, and I believe it shows what our whole navy is.³

Gen. Banks visited the camp the other day. We fired the salute from our battery. We used 10½ lb. cartridges. You had better believe they talked some.

Remember me to all the folks in Chicago, our folks of course. Tell Mother I shall write to her next.

I received letters by yesterdays mail from Sarah Hunt, Sophia, Eunice, Rossie and yourself.

Write Soon, Jerry

1. Godfrey, or Gottfried, Weitzel (1835-1884) was born in Bavaria (Germany) and immigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio, with his parents. He graduated from West Point and was a career military officer working primarily as an engineer. In 1861 his company served as the bodyguard during the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln. Early in the Civil War he constructed defenses in Cincinnati, Washington, D.C., and for the Army of the Potomac. He then became the chief engineer on General Benjamin F. Butler’s staff. At this time he was commanding the advance in General Nathaniel P. Banks’ operations in western Louisiana and he will command a division under Banks at the siege of Port Hudson.

2. “On January 14, 1863, a combined expedition of Union gunboats, infantry, and artillery attacked the [CSS] Cotton near Pattersonville [Louisiana]. Her crew burned her and sank her across Bayou Teche as an obstruction. … Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Buchanan had command of the Federal vessels. He was shot in the head by one of the Confederate riflemen.” For more details, see page 105 of The Civil War Reminiscences of Major Silas T. Grisamore, C.S.A., edited and with an introduction by Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr. (Louisiana State University Press, 1993), available on Google Books.

Thomas M. Buchanan.

3. See our post of January 14, 1863, Battle of Galveston, for more details on Commander William B. Renshaw, the USS Westfield, and the USS Harriet Lane.